by DAVID AXE

Robert Grenier’s CIA diary ’88 Days to Kandahar’ recounts America’s errors in Afghanistan

Robert Grenier was the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency’s chief of station in Pakistan and Afghanistan on 9/11. In his new book 88 Days to Kandahar, he describes—in lively, clear prose—America’s two-month campaign to support Pashtun insurgents fighting to seize southern Afghanistan from the Taliban and, by extension, Al Qaeda.

It’s a quick, engaging and illuminating read—and not a little depressing, as Pashtun warlord Hamid Karzai’s victory over the politically and tactically inept talibs leads, almost inexorably, to Karzai’s own inept rule … and the Taliban’s resurgence, which in turn draws the United States into a protracted ground war.

“History, viewed in hindsight, takes on the trappings of inevitability,” Grenier writes. But in the present, it’s a chain of small battles, each seemingly critical in our effort to shape the world. Grenier’s account of the Pashtun campaign captures the urgency he, the Afghans and millions of Americans felt in the months following 9/11.

88 Days to Kandahar is easily one of the best war books in recent years. What follows are just a few of its revelations.

Grenier traces America’s problems in Afghanistan back to the “Pressler Amendment,” a 1985 U.S. law that mandated that the U.S. president annually certify that Pakistan did not possess nuclear weapons. When Pakistan got nukes and Washington finally started enforcing the Pressler Amendment, the United States abruptly cut off much of the aid on which Islamabad had come to depend during its long shadow war against Soviet troops in Afghanistan. Resentment among Pakistani leaders poisoned U.S.-Pakistani relations and helped drive the South Asian state—and indeed the whole subcontinent—toward religious extremism.

Grenier and his people tracked Osama Bin Laden in the months before 9/11. Pro-U.S. Pashtun tribesmen offered to kill the Al Qaeda leader for the Americans. “They proposed to bury a huge quantity of explosives beneath one or more of these road junctions [Bin Laden routinely traveled],” Grenier writes. But CIA policy forbade assassination. “We had to tell them to immediately stand down.”

After 9/11, Washington empowered the CIA to take down Al Qaeda in Afghanistan, with Afghan tribesmen acting as American’s foot soldiers. Grenier quickly discovered that his biggest enemy wasn’t the Islamists, but his agency’s own Counter Terrorism Center and its leader Cofer Black. “CTC often exhibited little understanding of the cultures, institutions and social and political dynamics of the regions where … terrorists operated.”

Grenier advocated supporting restive Pashtuns in southern Afghanistan, the Taliban’s seat of power. CTC wanted to focus American resources on the Northern Alliance, an anti-Taliban force on Afghanistan’s northern fringe. “The Taliban was a southern problem; the solution lay in the south,” Grenier explains.

Grenier advocated supporting restive Pashtuns in southern Afghanistan, the Taliban’s seat of power. CTC wanted to focus American resources on the Northern Alliance, an anti-Taliban force on Afghanistan’s northern fringe. “The Taliban was a southern problem; the solution lay in the south,” Grenier explains.

By Sept. 18, 2001, with the U.S. threatening all-out war, Grenier practically begged Taliban chief Mullah Omar to turn over Bin Laden and spare the world a grinding conflict. But Omar refused to budge. “If war comes, it is the will of God,” Omar said. Besides, by then Bin Laden had gone into hiding and, according to Omar, even the Taliban would have a hard time finding him.

The British were eager to help the CIA in Afghanistan in the weeks following 9/11, but their ideas were terrible. CTC urged Grenier to put into action a British plan to send a British-trained Pakistani narcotics-enforcement team into Afghanistan as the vanguard of an anti-Taliban invasion. Grenier squashed the scheme, noting that “the one occasion that the unit in question had crossed the border to attack drug-processing labs, it had been surrounded by a drug militia, captured and its members sent back across the border minus their weapons and most of their clothing.”

More than once in late 2001, the Pentagon launched pointless, risky operations in southern Afghanistan for no other reason than to try proving the conventional military’s relevance in a campaign dominated by the CIA, Army Special Forces and the Pashtuns. One Army Ranger attack targeted Omar’s empty compound, which the Taliban leader had abandoned amid U.S. Air Force bombing runs in October 2001. One Ranger was wounded when nearby talibs opened fire, and two Rangers died when their helicopter crashed. All for nothing.

Grenier pleaded with the Air Force to keep Pashtun anti-Taliban fighters—Karzai, in particular—supplied with weapons and ammo. But the Air Force C-130 transport crews wouldn’t fly low owing to the possibility of Taliban ground fire, and the flying branch’s parachute riggers had lost the specialized skills for dropping bundles from high altitude. The Air Force refused to let CIA riggers re-teach the methods. “We risked losing an irreplaceable tribal ally due to our inability to make secure airdrops, and all because of bloody-minded interagency politics,” Grenier laments.

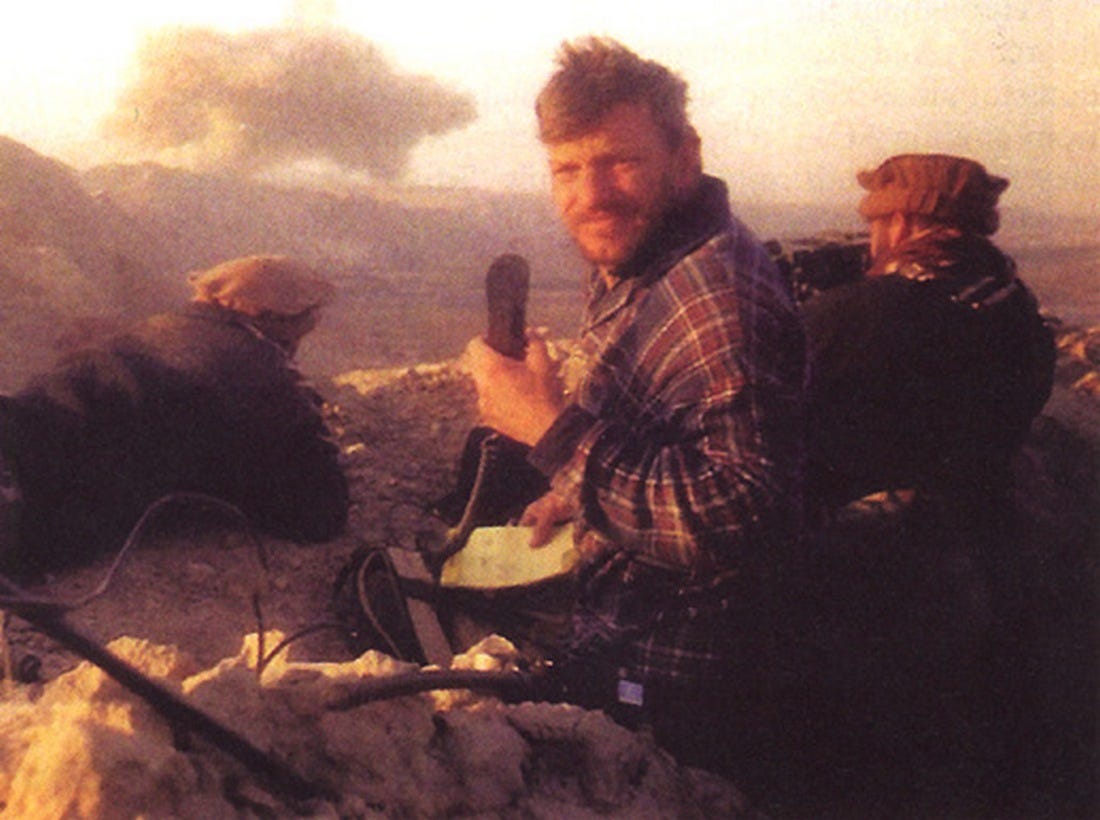

The CIA and Army Special Forces sent combined teams of agents and Green Berets into southern Afghanistan to help Karzai and other Pashtun fighters. But CTC did its best to limit the deployments, demanding that the Army cut the number of Green Berets so that, if Karzai got overrun, fewer Americans would die. One Special Forces captain flat-out ignored CTC’s directive and hopped onto a helicopter along with two of his troopers to join Karzai. “I very much feared for this young officer’s career,” Grenier writes.

U.S. warplanes flew top cover for the Americans and Pashtuns on the ground. CTC had the bright idea of dropping a 15,000-pound daisycutter bomb—then America’s biggest non-nuclear munition—to kill some Taliban fighters near Karzai’s own forces. “It was a terrible idea,” Grenier writes, noting that the blast would have killed, well, everyone in the area—not just talibs. Fortunately, he was able to nix the plan.

Grenier’s Pashtun strategy was beginning to work when, in November 2001, the U.S. Marines for some reason invaded southern Afghanistan, occupying a private airstrip outside Kandahar. The CIA was at a loss to explain the Marines’ move. “We were concerned about the Marines’ ability to distinguish friend from foe.” Happily, the jarheads just sat there … and didn’t interfere as Karzai’s tribal warriors finally ousted the Taliban.

As the new prime minister of Afghanistan, Karzai relied on the support of clashing tribes, religious sects and political constituencies. “He made promises he could not keep, which would ultimately undermine his credibility,” Grenier wrote. As Karzai’s regime—and its American backers—lost legitimacy, the Taliban returned in 2005. And the full-scale occupation that Grenier had fought to avoid become the United States’ bloody legacy in Afghanistan.

No comments:

Post a Comment